My 4th-Great-Grandfather in 1850: "Insane"

The barely legible word in the 1850 census that opened the doors to a family mystery.

In 1850, my 4th-great-grandfather, Collins Lovejoy Sr., was 66, a blacksmith, married, father of five, and a grandfather. And he was labeled "insane" in the census.

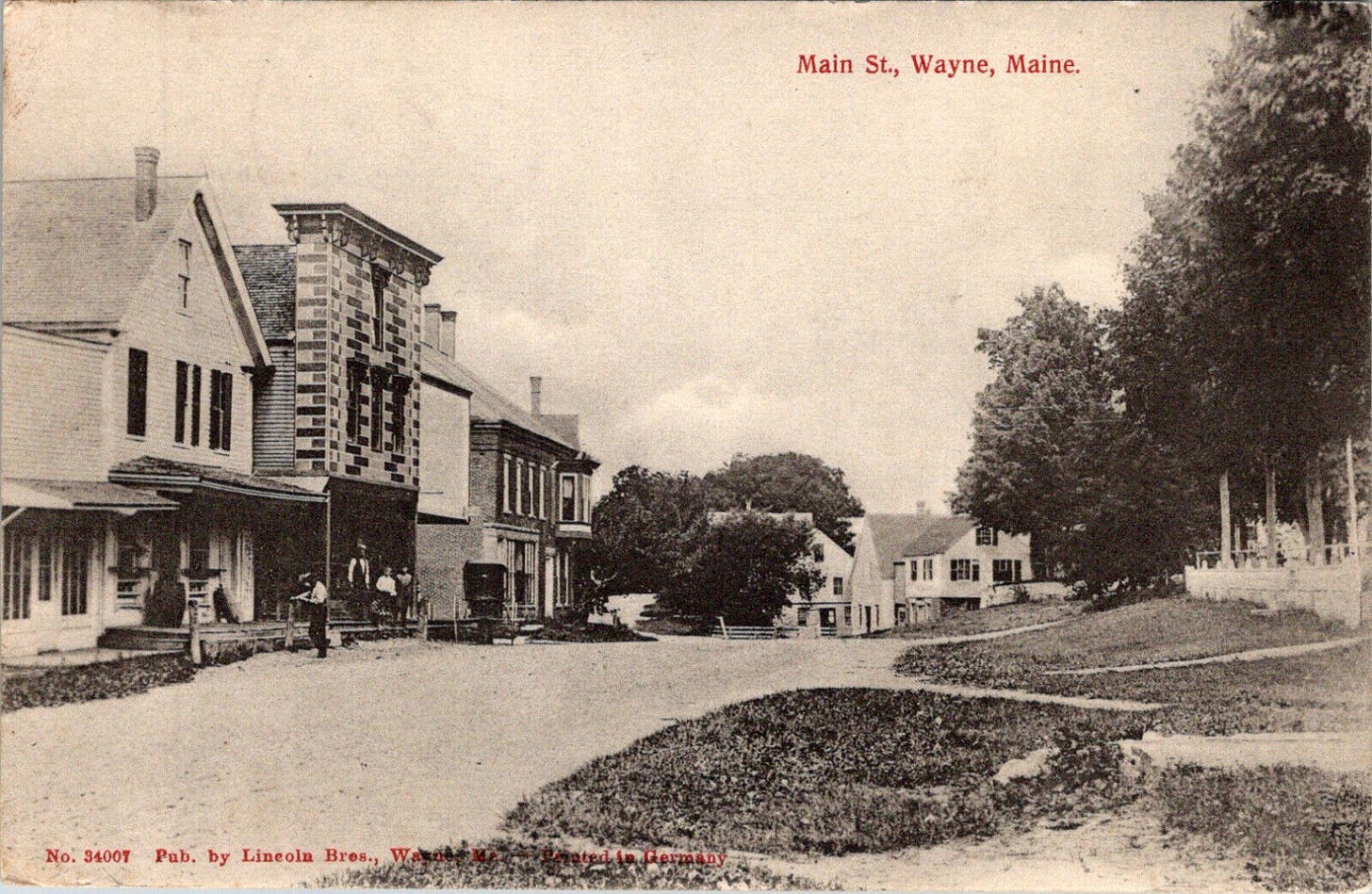

In 1840, the U.S. census featured a new question: “Is anybody in the home deaf, blind, insane, idiotic, pauper, or a convict?” Collins, 56 years old, apparently passed the test — the census taker didn’t mark him as any of the above. But ten years later, in 1850, things changed. The census taker marked Collins as one of only four legally “insane” residents of small-town Wayne, Maine (1,367 residents).

I remember almost missing this the first time I saw it. Was Collins really mentally ill? It’s difficult to say. In 1850, counting people with mental illness wasn’t scientific. There were no official definitions given by the government for insanity, and an understanding of what mental illness was then was a far cry from what we know today. Did the census taker make a questionable judgment call after an unusual interaction with Collins, or did he actually have a diagnosed illness?

There is, however, another suspicious clue. In the History of Wayne, ME, published in 1898, there’s a line that says, “[Collins Lovejoy Sr.] was removed by his son Collins [Jr.] in the year 1851 to Chesterville, where he continued his residence until his decease.” There’s no explicit reference to Collins’ insanity, but why would he leave his wife of 46 years, Sally, in Wayne, to go live with his son 20 miles away indefinitely? Collins died in Chesterville in 1855, but in 1860, Sally still lived in Wayne with her daughter and grandchildren at age 75. Did Collins’ condition become too much for Sally to manage? What did he suffer from, exactly? Earlier in his life he owned a hotel in Wayne, and the 1850 census listed him as a blacksmith. Did something suddenly change? Was there an accident?

Collins died five years after being marked insane, in 1855. I’m still hunting for a surviving death record that might give us another clue. For now, we’re left with what’s undoubtedly just the tip of the iceberg — that six-letter word “i-n-s-a-n-e” — and we may never know more. For now, we’re left with some scraps of evidence, a mystery and our imaginations.

Tip: Take special care to look at every question on census records — they change slightly every decade. For instance, in 1840, census takers marked down the “Number of colleges or universities, primary schools, and grammar schools” attended. In 1910, census takers asked: “Is the person a survivor of the Union or Confederate Army or Navy?” And in 1940, they asked, “Did this person receive income of more than $50 from sources other than money wages or salary?” If you want to start looking for your family in the census, start on Ancestry, MyHeritage, or FamilySearch and see what you can find!

Jack Palmer is a History and Psychology double-major at Duke University. I’ve done genealogy research since I was 10 and love writing about it for family, friends, and anybody else who might enjoy a blast from the past.